After visiting the church in which my great-grandparents were married by Gentleman Jim’s uncle, Gig, BK, and I drive the westward road, which rises to meet the Partry Mountain highlands and snakes toward the pastoral plateaus of Glennagashleen. There, we hope, to finally find the Gibbons Homestead, the sprawl of land where, long ago, the extended clan lived for generations.

As we gain elevation, the verdant farmland rushing by us gives way to rockier terrain, boggy patches, scrubby grassland, and rocky outcrops. The landscape, steep, ragged, full of cliffs, is suddenly dappled with grazing sheep.

The hillsides subtly reveal evidence of abandoned potato fields — or “lazy beds” — that were, for centuries, burrowed into this rigid terrain. Long ago, the West Ireland system of potato cultivation supported generations of Irish people before the devastating famine, which began in the 1850s, causing abject suffering and untold scores of death by disease and starvation.

Pulling off the road to breathe in the scene, I can hear only the rushing wind, the distant bleating of sheep, the collision of several interconnected streams, and — I believe — the soft voices of my distant family urging me on, telling me that I am getting closer to what it is I seek: home.

My Montana cousins, Gig and BK, stand with me, overlooking the valley of Glennagashleen, where — somewhere below — it’s said the Gibbons Homestead once (and, perhaps, still) existed.

Over many years, Gig and BK, experienced travelers, cartographers, and amateur historians, had made repeated visits to this land, searching for the family homestead. On one such sojourn, their best clue was secondhand information about the homestead standing near an old, abandoned tractor tire. From where we now stand, Gig points out the tire, ditched long ago against a crumbling rock wall, surrounded by old stone ruins and a flock of roaming sheep.

on the highway toward enlightenment.

The tire, Gig tells me, was a false lead, a dead end on the highway toward enlightenment. It happens a lot in Ireland, Gig says, where landmarks and anecdotes are provided by locals to help visitors find their ways back home, only to send the travelers in knotted circles. However well-intended, navigational assistance from Irish locals is just plain incorrect.

Laughing to see the old tire where he’d discovered it a decade earlier, cousin Gig says, “Not a lot changes here. It’s wrong today — just as it was back then!”

Since that foiled attempt to locate the homestead, Gig and BK had rolled up their sleeves and come up with more reliable guidance to the place we all sought. Their dogged persistence paid off. They found it!

The Gibbons Homestead is a place I had imagined almost all my life, and then, over the last six or seven years, deeply researched. It’s a critical location in the Fight for Glory story, the place where everything begins. My historical review had taken me back as far as my great-great grandfather, Richard Gibbons, who was a tenant farmer in the early 1800s on the land owned by an English landlord, Lord Plunkett, Protestant Archbishop of Tuam. I had seen some of this land in old photographs, read about it in archived newspapers and memoir, dreamed of it on countless nights.

But what I had imagined, I had to experience. This, the difference between tall tales and true stories.

Turning the car onto a gravel road that rises into rocky pasture and sheep-sprinkled hills, cousin Gig begins to smile. Before us, deeply-weathered, hand-built stone walls, the forest-peppered Partry Mountains with their jagged, rocky peaks. Stream banks and ravines, speckled with yellow-flowering bushes. The roar of whitewater, sparking with flashes of brown trout. The landscape, striking, but austere, gorgeous and harsh.

The Ridgeline circling the valley howls with icy-cold winds that bellow a mournful melody. Irish folklore says this is the song of screaming banshees and towering giants. In the distance, storm clouds huddle above stone ruins as if to mark the spot like the old star in the New Testament.

“This is the place,” Gig says. “You’re looking for home. Here it is!”

In the valley below, as far as the eye can see, the Gibbons Family Homestead — acres of rocky hillsides, endless rows of potato ridges and furrows, which in the end, failed the clan no matter how close to breaking they worked their backs and bones.

I imagine my ancestors checkered on these hillsides, bent over from dawn to dusk, weathering cold and rain, at work in the hardscrabble, digging with hand and spade, planting, weeding, bleeding, as they harvested potatoes, day-after-day, year-after-year, just to survive, hoping to make it to church on Sunday in Partry, or to a candlelight vigil under cover of night.

I listen to the wind to hear their voices. Perhaps they speak to me. I believe they do, and Fight for Glory is so much richer for their song.

As my eyes well up with tears, it suddenly hits me: after two centuries, this land must be virtually unchanged. In a world where everything rearranges quickly, often overnight, this place, where my family began, stands immutable. Some of the stone walls have crumbled or worn away. Unkempt fields of grass enshrine fenceposts and a toppled chimney. The land is untended now, and has been for decades, but what was gone can still somehow be seen, felt, experienced.

The rain, suddenly coming down in torrents.

Against the elements, I descend into the valley, approaching the homestead built centuries ago by my great-great-grandfather, Richard Gibbons. I find a rock wall at the back of the property that still stands, though imperfectly, in the shape of a doorway. I bend a knee and kiss the cold, wet stones and say a prayer of gratitude.

I enter the framework of the old house, approaching a flat-stoned hearth where, long ago, a roaring fire must have warmed my ancestors. The indelible scent of peat logs — saltwater, wet earth, dried grass, and pine — still lingers over the property. The burn of history. The forge of truth. Here, where my family once loved, struggled, sang, and told stories. Here, the place they also left.

Nearby, in the middle of a wide, but shallow stream, I lay eyes on a stack of rocks I’d read about many times, markers of my great-grandfather’s favorite place to snatch brown trout from rushing currents with his bare hands to feed his wife and children, despite the risk of incarceration (since the fish, as all animals, belonged to England the Queen).

River Aille - Glennagashleen, County Mayo - Ireland

A five-minute walk away, the rugged edge of the River Aille, where — the story goes — my great-grandfather Thomas John Gibbons defended his sister against the alcohol-fueled fists of her husband, the traitorous Mocky Dolan. A fight to the finish, or nearly so, Dolan beat my great-grandfather with rocks in his hands, then kicked him into the river to die.

Only a last-minute rescue by close friends and neighbors, Phillip Derrig and Michael Cusick, saved my great-grandfather from certain death. By torchlight, he was pulled from the waters and ferried in a horse-drawn cart to the port of Galway. That very night, the Gibbons Clan left Ireland forever.

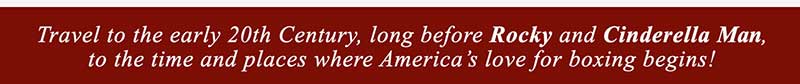

They came to America. Mike Gibbons, the St. Paul Phantom, is born three years later in 1887. Tommy Gibbons, The Happy Warrior, comes to life four years after that.

Thomas John and Mary Burke Gibbons

St. Paul, Minnesota - America 1890s

from a boxing tour of England, diverts instead to Ireland

to confront his father's nemesis, uncle Mocky Dolan.

Gibbons Homestead, Glennagashleen - 1920

According to family stories, my great-grandfather often remarked, “What matters most is what you do next.” I’ve carried this wisdom close for most of my life, but in my visit to Ireland and the family homestead, lost for decades and suddenly found again, I understand more completely what he meant.

When Thomas John Gibbons left home, this land on which I stand, he opened the door to a future inconceivable — to America, freedom, and the legends that two of his sons would forge in the Promised Land of the United States.

What my great-grandfather did a century ago was live the first chapters of Fight For Glory, then keep the story howling over space and time until I was, at last, ready to hear the music and record it.

Called to action by ghosts long gone, then tracking them from shadows into light, this is precisely what I’ve done.