“Once again, the great pendulum is swinging into sight.

The comet has returned…”— New York Sun, September 19, 1909

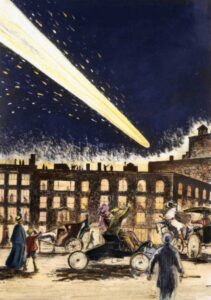

Every 75 years, she mysteriously returns to the skies — the comet. Halley’s Comet.

It’s 1910, and America’s coming up fast — the gold mined and rails laid, the coasts connected, skies scraped, and cities raised. The future, it’s already arrived. Everything’s possible, so anything goes.

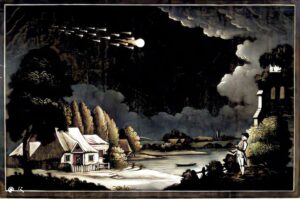

And here she comes again: the comet, surging toward earth, energetically charging past old stars, dark matter, cosmic dust, and unnamed constellations… Bursting through starlight and cloud, fog and vegetation. A verdant expanse of Oaks, Elms, Silver Maples. Moonlight in the mirrored surface of a pristine lake. A pair of Western Grebes skittering into flight over Minnesota’s Lake Osakis.

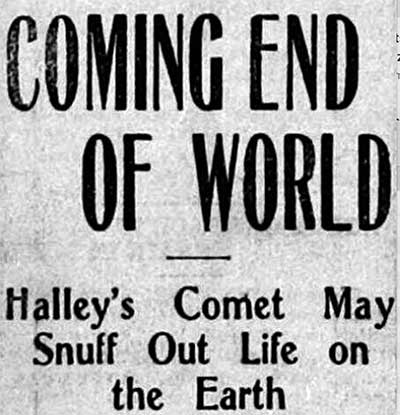

The Halley’s Comet Fever of 1910

by Steve Smith

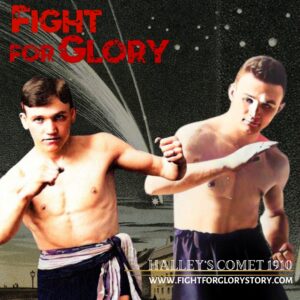

Then, amidst a clearing in the woods, the figures of two young men. Spectral at first. Haloed in fog, crowned by glades. Their movements, sleek, lightning-quick, powerful, but lighter than air. Almost immune to natural law, it seems. Dancing? No. The young men are trading blows — boxing, sparring, training. But merrily. Sportingly.

of Halley’s Comet in May, 1910

Jab. Jab. Feint. Glide. Straight left. Pop!

Tommy Gibbons, 19-years old, has more bulk than agility, but he’s game, exuberant, indefatigable, a worthy shadow to his older brother. And Mike Gibbons, 23-year old, compact, but statuesque, lithe, his movements elegant, fluid, and feral by turns. He hasn’t yet dreamed a fistic trick he can’t persuade a padded mitt to play.

Above them, the comet. They can almost hear it, feel it. They are not alone, the comet wails, not ever, not in their suffering. Nor in their dreaming.

The cyclical arrival of Halley’s Comet has long been perceived as a dark omen — a harbinger of the deaths of kings and princes. Throughout history, the comet’s return has uncannily illuminated the assassinations of Julius Caesar, President James Garfield, and Czar Alexander II, the death of Napoleon, and numerous other heads of nations.

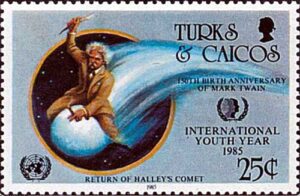

Mark Twain, timed his life clock to the comet with precision or fate. He came into the world beneath Halley’s bright tail in 1835, and laid down his pen and left for good upon its reappearance in April 1910, exactly 75 years later.

1835 – 1910

In the year 66 AD, Saint Peter bore witness to the comet overhead, which lit Jerusalem’s fall to the Romans and the destruction of Christ’s second temple. In 451, the comet blazed the path of Attila the Hun, bringing ruin to Rome. In 1222, the savage Mongol conqueror, Genghis Khan, ravaged China, Persia, and India, the comet’s light guiding — and igniting — his conquest of the world. In 1456, Halley’s Comet rallied through space and time, and Athens fell. The Pope directed that the nightly prayers of Catholics should be amended: Lord, save us from the Turk, the comet, and the devil.

Jon Powell, BBC Sky at Night

With astrology in 1910 still holding more academic heft than the comparatively nascent field of astronomy, the cultural panic button was in for a pounding so fierce with Halley’s Comet that it would eventually short circuit. A combination of faulty stargazing, media ballyhoo, and mob mentality teamed to position humankind for a collective nervous breakdown during the comet’s 1910 joyride.

Tabloids circulated rumors that Earth would be obliterated when it passed through the comet’s tail, while soothsayers and fortunetellers consulted their crystal balls with ferocious devotion and unwaveringly alarming results.

The ominous tail, the New York Times reported, “will emit cyanogen gas that will impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet.”

“This year, 1910, will be one to look back to with trembling. The coming of the comet will affect us for the worse,” said self-proclaimed prophet Madame de Thebes. “The strain of the stars will be most severely felt in America. The people of America will have to pay dearly for all their riches and sudden prosperity.”

inflamed coverage of Halley’s Comet

Human beings responded to the dire prognostications with a rather desperate lack of moderation. Some Americans, steeped in overwhelming anxiety, took their own lives. A rancher in California crucified himself in a cornfield, nailing both feet and one of his hands to a homemade wooden cross. Minnesota farmer John Marlow dug a deep subterranean cave in his backyard, fitted with an air-tight door to keep out the comet’s presumably poisonous gases. “In addition to himself and his family, (Marlow) will take two horses, two cows, a dog, a cat and a number of chickens into the cave,” reported the St. Paul Pioneer.

In a winsome romantic gesture, some coal miners refused to work their shifts during Halley’s airborne journey, preferring to perish above ground with their families. Some watched the comet from hot air balloons or the penthouse suites of New York skyscrapers. A million people in Constantinople took to their rooftops, huddling together for comfort, praying for salvation.

The fiery light of Halley’s Comet in 1910 changes everything — and everyone — in the FIGHT FOR GLORY Universe, too.

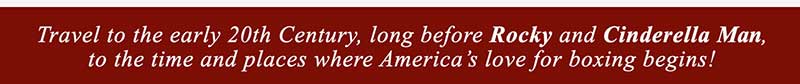

Boxing, which has been illegal in most of the United States for three decades is suddenly legalized in New York.

Former lightweight champion and fistic mage Joe Gans — The Old Master, they called him — races home to die of tuberculosis in his mother’s arms. He’s 34-years old.

Middleweight Champion Stanley Ketchel — The Michigan Assassin, they called him — cleans up after bedding a ranch girl, sits down to breakfast, and is shot dead with his mouth full by the ranch girl’s jealous boyfriend. Suddenly, the middleweight boxing crown is up for grabs!

On Independence Day, a desperate battle for racial supremacy and the heavyweight championship — The Fight of the Century, they called it — is staged in Reno, Nevada, pitting the “unforgivably black” Jack Johnson against challenger and Great White Hope Jim Jeffries.

Approaching fight day, Johnson expresses on April 14th in the El Paso Times, “That there Halley’s comet is the cause of all my good luck,” said Johnson from Chicago yesterday. “Why, it is the happiest star in the sky and it brings just the best luck that could ever happen. I shore wish that comet would stay around till July 4…”

And on the shores of Minnesota’s Lake Osakis, two figures — Mike and Tommy Gibbons — spar beneath the radiant light of Halley’s Comet. Mike, the new welterweight phenom of the Twin Cities, shares Jack Johnson’s sentiment.

“So is this really it, Mike? The end of the world?” Tommy asks his big brother, a balance of worry and amusement. “Is the comet really how we meet our doom?”

“Nah, Tommy Boy,” Mike grins. “This is no ending. It’s a goddamned invitation!”

The comet, she listens. Fight day arrives in Reno. Johnson triumphs handily against the Great White Hope. Jack’s world heavyweight crown is now undisputed.

At that very same moment, seventeen-hundred and sixty miles away in a packed Minneapolis gymnasium, Mike swiftly sinks his left glove into the face of Jack Parres, the Iron River Kid, in a fight scheduled for 10 rounds, but it concludes with this single blow in the third.

For Jack Johnson and Mike Gibbons, she’s a lucky star, indeed. And in time, these fighters’ fistic tails will cross. Glory be!