Ballynaslee Township, County Mayo - Ireland

Joined by my Montana cousins, we wound our way from the village of Westport across the verdant countryside — bogs, scrubby woodlands, rocky outcrops, all of it a deeper green than even L. Frank Baum could have envisioned for his Emerald City of Oz.

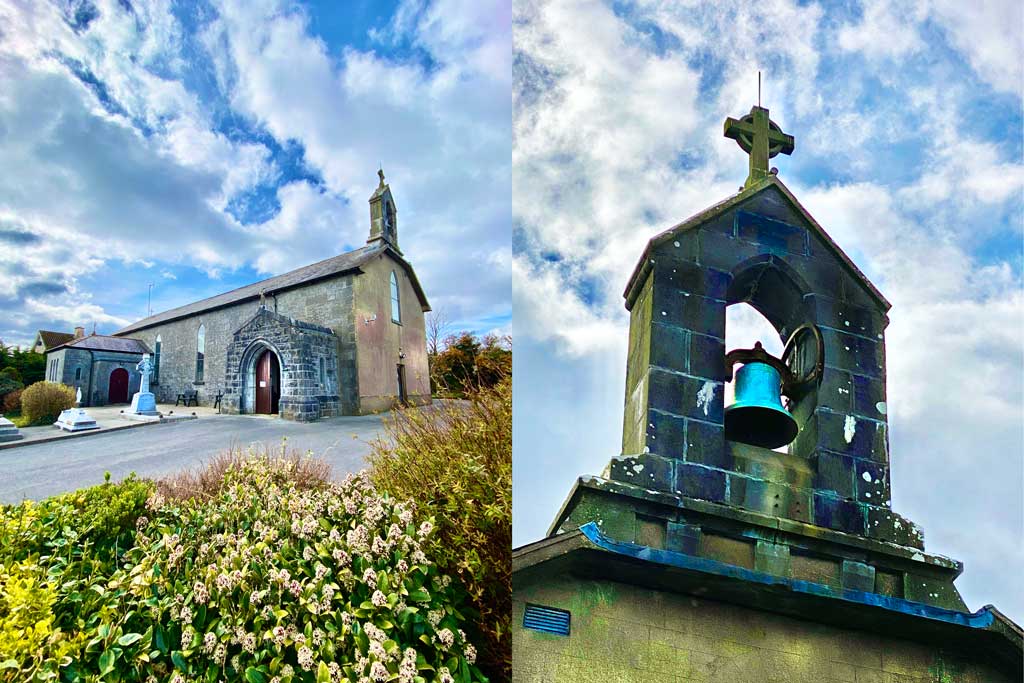

We were on the hunt for the stone church in the Partry Mountains where old family journals, letters, and records indicated my great-grandparents were long ago married.

On a hilltop perch somewhere between the shoreline regions of Lough Carra and Lough Mask, we found St. Mary’s Catholic Church — built sometime in the 1840s as an act of rebellion against British rule, which outlawed my family’s faith. Beyond a landscaped garden and burial ground, crypts adorned with Celtic crosses and marble crucifixes, the stone chapel with limestone walls stood still. At the apex, a cast-iron bell. I wondered when the bell was last rung, how its song might have changed in 150 years, and what music it would have for me now.

Family legend suggested there might be at St. Mary’s a clear and defining link between my great-grandparents — who, after hard lives of British oppression, famine, hunger, and strife, were weary of conflict and abhorred fighting — and the world of professional boxing. Most specifically, family lore crackled with possibly apocryphal connections between the Gibbons and the Corbett Clans, with St. Mary’s as their point of intersection.

I’d heard the stories, but as we all know, not every story is a true one.

IS the Family legend True?

World’s 2nd Heavyweight Champion

To the uninitiated, the name Corbett might mean very little, but years into my deep study of the fight game, the dead man’s name howled with intrigue.

In the 1890s, there was a heavyweight boxer in America, a pugilist of Irish descent (as so many fighters of the period were), named James J. Corbett.

The world called him “Gentleman Jim,” and credited him with introducing a “scientific” approach to boxing, in which technique trumps brute force.

In Fight for Glory, I describe this style of boxing — long ago dubbed “The Sweet Science” — as “fencing with fists” or “chess with padded gloves.”

Rather than a blunt devotion to throwing sledgehammers in the ring, Corbett’s style of boxing — which my grandfather, Tommy, and great-uncle, Mike, mastered and made famous in the United States — embraced strategy and wit, footwork and feinting that not only yielded great victories for its proponents, but often spared them the grisliest costs of fisticuffs.

World’s 1st Heavyweight Champion

It was with a virtuosic deployment of this scientific boxing in New Orleans, 1892, that “Gentleman Jim” Corbett defeated the more animalistic heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan — the Boston Strong Boy, they called him — in the 21st round. This victory made of Corbett the world’s second heavyweight boxing champion.

In later years, both Corbett and Sullivan would inspire, influence, and endorse Mike and Tommy Gibbons as maestros of “the sweet science,” this method of elegant warring.

(Philosophies outlined in Sun Tzu’s ancient combat manual, The Art of War, are, by many accounts, at the crux of “the sweet science.” Latter-day fighters like Tyson Fury, Floyd Mayweather, Jr., Anthony Joshua, and Manny Pacquiao carry on the scientific tradition of hand-to-hand combat).

Now, a century and a half after these family legends were born, I’m approaching the church myself, crossing burial grounds where former priests were laid long ago to rest in stone crypts with carved markings. One of these graves stands out to me above the others, utterly commanding my attention. Marked with a dragged-cut limestone Celtic High Cross and the inscription “Lord have mercy on his soul,” this tomb belongs to Reverend James Corbett.

At last, tentative verification of the family stories that St. Mary’s Church was presided over by James Corbett, already confirmed by genealogy records as uncle to Gentleman Jim and the man of God who married my great-grandparents, Thomas John and Mary Burke in 1872.

The legend of the church, according to the unpublished family memoir, Fifteen Rounds with Tommy Gibbons:

“It was when Gentleman Jim Corbett made his barnstorming victory tour through Europe and the British Isles that he came to his uncle’s parish and donated to the church the bell in the tower… Later in life, Jim Corbett married outside of the Catholic Church. His uncle, St. Mary’s priest, was so grief-stricken that he silenced the bell. When Gentleman Jim, on his deathbed, reconciled his Faith, the bells tolled once again through the hills of St. Patrick.”

I smiled to myself, comforted by the idea that bells long silent might one day ring again. I was counting on it. It’s why I’d come to Ireland in the first place.

answered prayerS and gratitude

were married by Rev. James Corbett here in 1872.

are memorialized in this sacred place.

Walking into the hushed empty sanctuary of St. Mary’s is almost unreal to me.

My footfalls echoing softly against the narrow-walled chamber, I drift past 18 rows of wooden pews toward a simple limestone altar draped in royal purple and accented by potted sunflowers. The sacred chancel is framed by an elegant, lancet-shaped “Trinity Window” of stained-glass, backlit by the morning sun. On either side of me, stained-glass windows, six in all, extend nearly floor to ceiling. One, in particular, vibrantly depicting the risen Christ in deep reds and streaming gold, catches my eye.

At the bottom of this window, a small inscription from its donor. The adjacent window too — a Virgin Mary draped in royal blue robes — is marked as a gift from Gentleman Jim himself: James J. Corbett, USA, 1891.

in 1891, confirmed the Gibbons family legend as true.

For a long while, I sit inside St. Mary’s, considering how some stories, like the one about my great-grandparents being married by a blood relative of American boxing royalty, are true. More than a century ago, my great-grandparents stood in this place before God, their marriage arranged for the larger family’s benefit as was common then, their vows exchanged, paving the way for everything that would come next in the history of the Gibbons Clan.

Before I depart, I make donations, light votives, select a vial of holy water, pluck a forgotten rosary off the bench as I kneel to pray for my daughter, my family, my friends. I ask God for guidance and blessings on the journey ahead, overwhelmed with a very real understanding that my very existence is reliant on what happened on this sacred ground several lifetimes ago and that maybe — somehow — everything is connected.