“Boxing is like jazz.

The better it is, the less people appreciate it.”George Foreman,

two-time Heavyweight World Champion

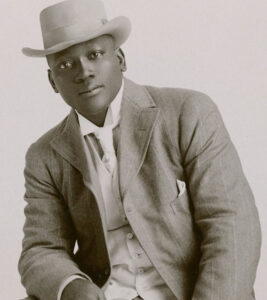

Jack Johnson — The Big Smoke, many called him — was the world’s first Black Heavyweight Champion of the World, winning the crown from Tommy Burns in 1908, defending it in 1910’s Fight of the Century against Great White Hope Jim Jeffries, and finally losing it in 1915 to Pottawatomie Giant Jess Willard.

During his heavyweight reign, the world-famous Johnson lived extravagantly and unapologetically, indulging in hot jazz, fast cars, fine dining, and white women. (He married three of them). In a world where skin color drew hard boundaries and often lethal rage, Johnson refused to conform.

He was, according to famed PBS documentarian Ken Burns, “the most famous and the most notorious African-American on Earth.” Even under constant threat of racist attack, police harassment, and physical violence, Johnson would give no quarter.

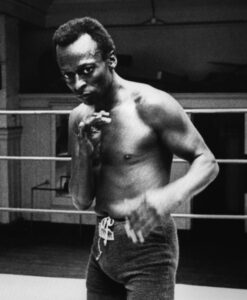

Jack Johnson was the kind of man Miles Davis — one of the most revered and influential jazz artists of all time — idolized.

He reminded others of an ancient warrior

“Jack Johnson was one bad motherfucker,” Davis says in a 1971 interview. “He was the heavyweight champion of the world and he was black, and that’s what it’s all about. The more (America) hated him, the more money he made, the more women he got, and the more wine he drank.”

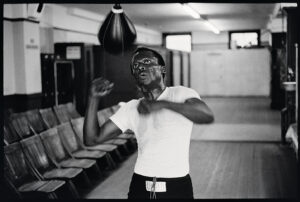

Davis was a lifelong fight fan, holding the boxing’s early-20th Century glory days particularly dear. “Boxing was no joke to the jazz legend, who died in 1991,” writes New York Daily News. “He was a student and a practitioner of the sweet science, watching films of old champions and emulating their moves.”

Davis worked out often in Brooklyn’s storied Gleason’s Gym, claimed to have sparred once with Roberto Duran. He got good, but refused to take a formal fight for fear of injuring his hands or lips — key tools in his “day job” as pioneering jazz trumpeter. So instead of fighting, he simply studied hard, worked hard, improved his fingering chops.

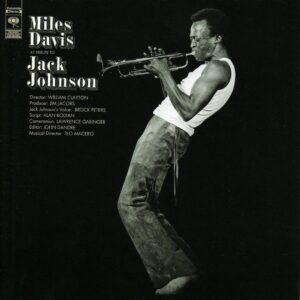

PHOTO: Glen Craig

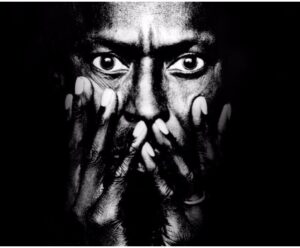

Over time, Davis incorporated some ring habits into the musical arena, wearing shoes a size too small (as a prizefighter often does) to keep him physically aware of his grounding. In later years, his health routine was nearly monastic. He did not eat, drink, or make love before a live performance. Instead, often, Miles Davis would shadow box in his dressing room until it was time to take the stage.

Boxing, Davis says, was “like practicing a musical instrument; you have to keep practicing, over and over and over again. A lot of people tell me I have the mind of a boxer…”

When boxing promoter and fight historian Bill Cayton needed someone to score the documentary about Jack Johnson he was producing with Big Fights, Inc. partner Jim Jacobs, he wanted a maverick, a visionary, a latter-day Johnson — someone capable of a livewire sound, something with power and style, unexpected and unpredictable. Only one name came to mind: Miles Davis.

and jazz in equal measure

from the late 40s through the 60s.

Cayton pitched the soundtrack for Jack Johnson to Davis after a Gleason’s workout. It was kismet. To prepare for writing the film’s soundtrack, Davis spent a full week mining the vast Cayton-Jacobs vault of old fight films. “He would discuss boxing with an intensity that you can’t imagine,” Cayton tells Daily News in 1996. “He’d come to our offices and ask for a bunch of films. He’d put the spool on the projector himself, threading the projectors, then sit there and watch for hours.”

Davis immersed himself in the heavyweight champion’s world, poring over films and photos of Jack Johnson in and out of the ring. He wanted the boxer’s spirit and movements burned into his mind as he set to composing — seeking, sonically, “that shuffling movement some boxers use.” At the time, Davis reportedly slept with a photo of Johnson next to his bed.

Some might say that Davis’ devotion to his mission was a summoning of sorts of The Big Smoke. Whatever it was, it worked brilliantly.

The ’71 landmark album considered one of Davis’ best

In two powerhouse recording sessions — February 18 and April 7, 1970 — Davis and a carousel of virtuosic sidemen (guitarists John McLaughlin and Sonny Sharrock, keyboardists Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, bass clarinetist Bennie Maupin, and drummers Jack DeJohnette and Billy Cobham) recorded more than three-hours of music that dived “even deeper into the jazz-rock vein of experimentation he had begun a couple of years earlier,” according to Daily News. Throughout recording, Davis often asked himself, “is this music black enough, does it have black rhythm, can you make the rhythm of the train a black thing? Would Jack Johnson dance to that?”

The 52-minutes of music on Davis’ Jack Johnson, released February 24, 1971, is widely considered a masterpiece of jazz fusion, blending elements of rock and funk with Davis’ signature trumpet sound. It’s been called “the purest electric jazz record ever made.” Music critic Tom Hull names it one of the “true highlights” of the trumpeter’s electric period and one of his best albums. It’s entirely possible that Jack Johnson would have danced himself weary to it.

Side one of the vinyl LP features a three-piece suite called “Right Off,” a medium uptempo driver with a strong rhythm and blues backbeat. The song also features a vocal sample of Jack Johnson speaking, which adds an extra layer of meaning to the song.

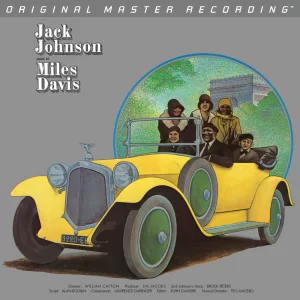

original master recording

Side two features a slower trio of interconnected tunes collectively named “Yesternow,” which begins more quietly, loping into a swampy jam, drums and bass hardening to a gutsy rock & roll vibe. “The solos float and weave above a very basic rhythm pattern,” according to a 1971 Newsday review, “each soloist playing until he feels he has made his statement.” Davis’ trumpet is sometimes “a mournful sigh,” and other times, “a soaring, piercing frenzy of sound. “Yesternow” builds to a pulsing finish, replete with electronic effects, wah-wah guitars, and phasers, yielding an almost psychedelic effect.

Davis himself was pleased of the work, even proud of it. Though Davis’ work was critically lauded and the Jack Johnson documentary was Oscar-nominated, the album was barely promoted by Davis’ label, Columbia, and faded into semi-obscurity.

— James Parker, The Atlantic – July/Aug 2016

Oliver Barrett, illustration

In 2003, Cayton and Davis’ longtime producer Too Macero teamed up to release the five-disc compilation, The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions, which reminded the world of the greatness of Davis’ work in a more enduring — if posthumous — manner.

James Parker writes in The Atlantic, “Between 1968 and ’75, Miles plugged into the musical zeitgeist and opened his music to distortion and groove-based repetition, either transcending or repudiating his roots in acoustic jazz.” Parker ends with, “Because while he was plugged in, while he was sizzling, he opened strange doors that—to use a line from another mutant, David Bowie—we’ll never close again.”

Miles, like Jack Johnson, was a heavyweight in his own beautiful way. And they shared much more than love for the fight game. Johnson was also a huge jazz fan as were nearly all boxers of the period. Well before Miles was born, Jack sponsored jazz, stride and swing musicians at his infamous 1912 Chicago “black and tan” club, Café de Champion. In the 20s and 30s, after his fighting years were over, Jack was performing Jazz on the vaudeville circuit in New York City, New Jersey and surrounds.

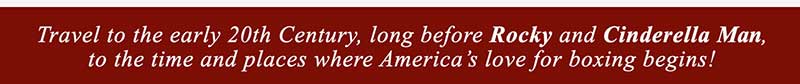

(ASIDE: The fighting family at the core of FIGHT FOR GLORY, my great uncle and grandfather, Mike and Tommy Gibbons, were top-tier boxers of the age and close friends of Jack. They’d visit Johnson’s Chicago club when the train sent them through the Windy City, and again in the twenties, they’d catch his Broadway shows and theatrical revues in Gotham when they fought at Madison Square Garden. But, this story and more related, are for another time.)

This compilation of Jack Johnson’s music and boxing, Tiger Rag from 1929, is a classic treasure that should not be missed!

Miles’ homage album to Jack Johnson, is indeed, an enduring sonic tribute that will weather the ages. In its glowing 1971 review of Davis’ boxing-themed masterpiece, Newsday concludes: “Miles’ music communicates the raw energy and frantic complexity of what we have been told of Johnson’s life.”

We couldn’t agree more!