"This contest of men with padded gloves on their hands… is no superficial thing,

a fad of a moment or a generation…

It is as deep as our consciousness,

and it is woven into the fibers of our being.

It grew as our very language grew.

This is the ape and tiger in us, granted.

We can’t get away from it.

It is the fact… We like fighting —

it’s our nature."-- Jack London, American author,

Call of the Wild

Anonymous (19th Cent)

As Adam raged against temptation in The Garden, as Cain slew Abel, as David faced Goliath, as heroes of The Iliad brutally sparred, as “The Big Smoke” Jack Johnson met “Great White Hope” Jim Jeffries in 1910 over color and crown, humankind has always been filled with a desire so hot it must be battled over.

We yearn. We burn. We toss and turn. We want, so we war.

Desire: why we fight.

In other words, we’ve always been raising fists at one another. Perhaps that is because it is in our nature.

19th century American essayist, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “Man was made for conflict, not for rest. In action is his power, not in his goals but in his transitions man is great.” From its inception America has remained a nation ripe with transition.

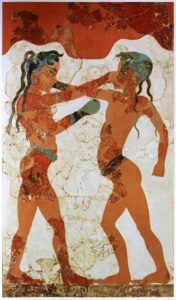

Greece (1700 BCE)

America — a nation of immigrants, first people, and old money, dreamers, makers, takers, and breakers, human beings seeking second chances in the Promised Land. The tired, the poor, the huddled masses yearning to breathe free. Indian tribes, bluntly battered to the brink of extinction. The black man, freed from slavery, but relentlessly hunted, haunted, and pummeled by a renaissance of racial fury. The Irishman, mocked, tromped, and starved in America, just as he was on the famine plagued island he fled for better days.

Every man had his dream, so every man had his fight.

“The history of the ring is the story of young men squaring up to (what they’re told they can never have), some paying the ultimate price for a burning desire to escape their surroundings,” writes Michael Prestage in Celtic Fists. “In the main, those who box chose to do so because they have a stark choice – it’s boxing or the coal mines.”

– circa 1550 (au Louvre)

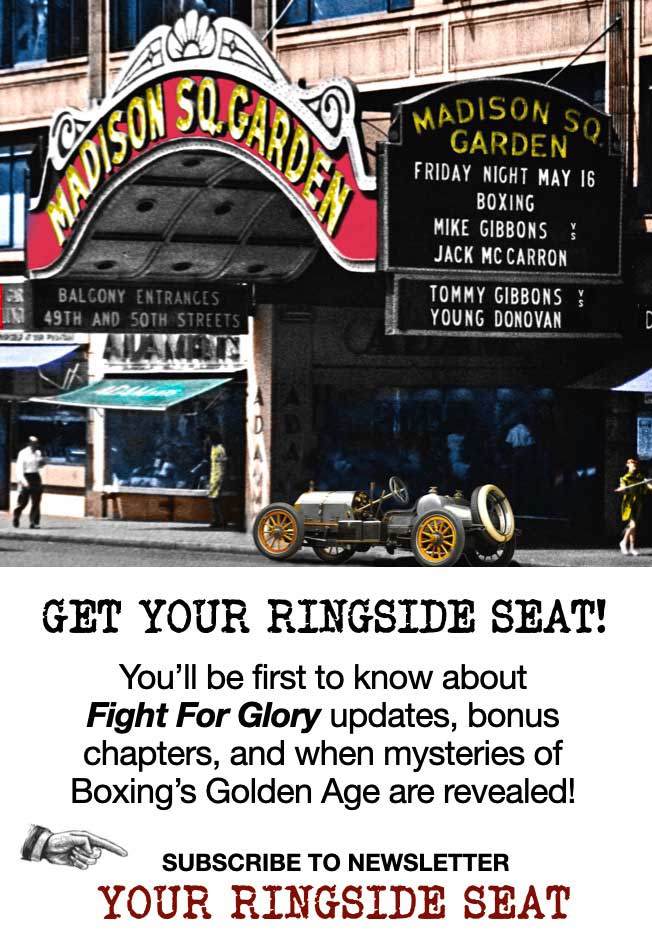

The math was simple: an immigrant and his sons might earn a dollar a week in the mines, railroads, or lumber yard.

Or he could win a hundred of dollars in a single, hour-long boxing contest.

By the 1920s, the heavyweight boxing championship of the world was worth more than $250,000 (or nearly $3.7-million, adjusted) to a man.

“Any fighter, champion or not,” writes the late, legendary sports journalist John Lardner, “enjoys a special kind of power and prestige.”

Ah yes! Boxing: how a man could change his stars.

In “Why We Fight, Part 2,” we’ll look at how Boxing reflected and organized the chaos of the early 20th Century.